Medical device and MedTech insights, news, tips and more

Self-Healing Slippery Surface Coatings for Medical Devices Could Help Thwart Infections

November 2, 2016

Implanted medical devices like catheters, surgical mesh and dialysis systems are ideal surfaces on which bacteria can colonize and form hard-to-kill sheets called biofilms. Known as biofouling, this contamination of devices is responsible for more than half of the 1.7 million hospital-acquired infections in the United States each year.

In a report published in Biomaterials today, a team of scientists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) at Harvard University has demonstrated that an innovative, ultra-low adhesive coating prevented bacteria from attaching to surfaces treated with it, reducing bacterial adhesion by more than 98 percent in laboratory tests.

“Device related infections remain a significant problem in medicine, burdening society with millions of dollars in health care costs,” said Elliot Chaikof, MD, PhD, chair of the Roberta and Stephen R. Weiner Department of Surgery and Surgeon-in-Chief at BIDMC and an associate faculty member at the Wyss Institute. “Antibiotics alone will not solve this problem. We need to use new approaches to minimize the risk of infection, and this strategy is a very important step in that direction.”

The self-healing slippery surface coatings – known as ‘slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces’ (SLIPS) – were developed by Joanna Aizenberg, PhD, a Wyss Institute core faculty member, Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and the Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science at SEAS at Harvard University. Inspired by the carnivorous Nepenthes pitcher plant that uses the slippery surface of its leaves to trap insects, Aizenberg engineered surface coatings that work to repel a variety of substances across a broad range of temperature, pressure and other environmental conditions. They are stable when exposed to UV light, and are low-cost and simple to manufacture. The current study is the first to demonstrate that SLIPS not only limit the ability of bacteria to adhere to surfaces, but also impede infection in an animal model.

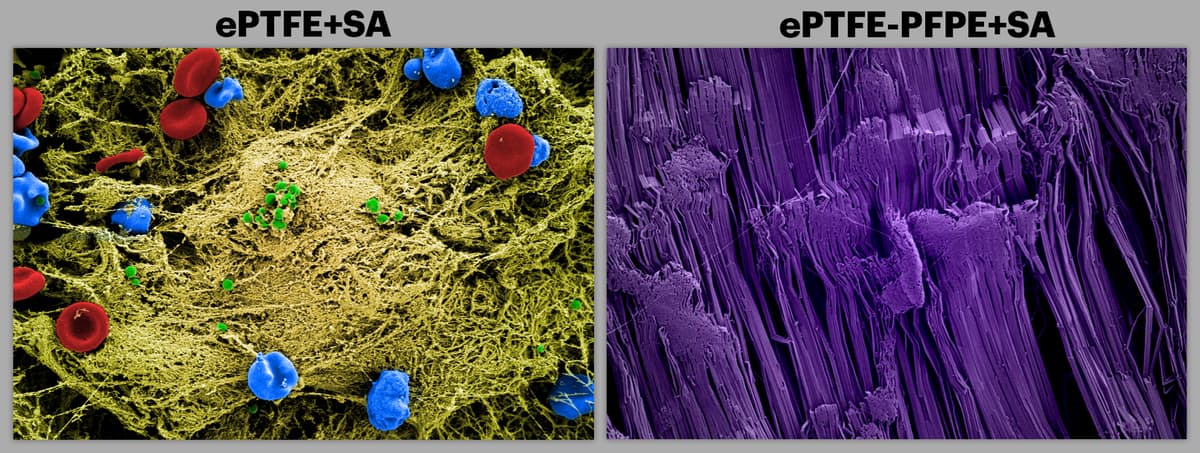

The SEM image on the left shows a commonly used teflon surface implanted into mice that were infected with S. aureus. The unmodified device surface attracted the infectious bacteria (green). Red blood cells (red), immune cells (blue), and extracellular matrix material (yellow) are also shown to deposit on the surface. The SEM image on the right (colored purple) is of the same teflon surface treated with SLIPS within the infected mice. It shows no adhesion of cells or deposition of extracellular matrix material.

“We are developing SLIPS recipes for a variety of medical applications by working with different medical-grade materials, ensuring the stability of the coating, and carefully pairing the non-fouling properties of the SLIPS materials to specific contaminates, environments and performance requirements,” said Aizenberg. “Here we have extended our repertoire and applied the SLIPS concept very convincingly to medical-grade lubricants, demonstrating its enormous potential in implanted devices prone to bacterial fouling and infection.

In a series of trials, the researchers tested three SLIPS lubricants for their anti-adhesive qualities. First, they incubated disks of SLIPS-coated medical material ePTFE – a microporous form of Teflon – in a broth of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), a generally harmless bacterium found in the nose and on skin, but one of the most common causes of hospital-acquired infections. After 48 hours, the three variations of SLIPS-treated disks demonstrated 98.3, 99.1 and 99.7 percent reductions in bacterial adhesion.

To test the material’s stability, the scientists performed the same experiment after soaking the SLIPS-coated samples for up to 21 days in a solution meant to simulate conditions inside a living mammal. After exposing these disks to S. aureus for 48 hours, the researchers found similar, nearly 100 percent reductions in bacterial adhesion.

Widely used clinically, medical mesh is particularly susceptible to bacterial infection. In another set of experiments to test the material’s biocompatibility, Chaikof and colleagues implanted small squares of SLIPS-treated mesh into murine models, injecting the site with S. aureus 24 hours later. Three days later, when the researchers removed the implanted mesh, they found little to no infection, compared with an infection rate of more than 90 percent among controls.

“Today, patients who receive implants often require antibiotics to keep the risk of bacterial infection at bay,” the authors wrote. “SLIPS coatings one day could obviate the widespread use of antibiotics and minimize the development of antibiotic resistant micro-organisms.”

“SLIPs have many promising medical applications that are in a very early stage of evaluation,” said Chaikof. “Clearly, there’s more work to be done before its introduction into the clinic, but this is one of a few studies that reinforces the exciting opportunities presented by this strategy to improve device performance and clinical outcomes.”

Source: Self-healing slippery surface coatings for medical devices could help thwart infection